Chowan University is a small Baptist school in Murfreesboro, a small town in the Albemarle Region that sits on the Meherrin river. The school was founded in 1848 as Chowan Baptist Female Institute, then a four-year women’s school. In the more than century and a half the school has been around, it’s seen many changes. The school began admitting men in 1931 and has changed its name several times, settling on Chowan University in 2006. Through the school’s many changes, it’s students still treasure their days at the school, and many loyally return every year for alumni days. But there’s one student who’s loyalty goes even further.

The Brown Lady of Chowan is said to visit her old dormitory every year on Halloween night, when the sounds of her brown taffeta skirts can be heard rustling through the corridors. And this is despite the fact that she died over a hundred years ago.

The story of the Brown Lady dates back to the late 19th century. According to the legend, Eolene Davidson was the beloved daughter of a wealthy family from Northampton County. Eolene was reportedly beautiful, friendly, kind, and loving, and with her family’s fortune she could easily have led a life of leisure. But she was determined to pursue an education and make something of her life. And so, in 1885, she enrolled at the Chowan Baptist Female Institute.

But the summer before she started classes, Eolene travelled to New York City to visit a friend of hers. In the months she stayed in the city, she became acquainted with a young lawyer named James Lorrene. The two soon found themselves spending more and more time in each others company. They shared similar interests, a passion for learning, and both were quickd-witted and enjoyed talking late into the evening. As September and Eolene’s scheduled return to North Carolina drew closer, the young couple realized that over the summer they had grown to love one another. One evening, James asked Eolene if she would marry him.

Eolene was torn. She truly loved James, but her desire to learn burned deep within her. And so she and James came to an agreement — the two of them would be married, when she completed her education.

And so Eolene returned from the excitement of New York to the quiet fields of Eastern North Carolina and began her studies at Chowan Institute.

Eolene was an eager student, and she threw herself into her studies. But she also soon became among her fellow students for her joy, her wit, and her kindness. She also became known for a distinct personal style, she seemed to own an unlimited supply of brown silk dresses. The voluminous brown tafetta she preferred made a distinct rustling sound as she moved through the halls. She was given the friendly nickname “The Lady in Brown.”

After completing her freshman year, the Lady in Brown returned home to her family. Her fiancee travelled down from New York to spend the summer, and he was immediately welcomed in by her family. Her parents could see that the two were a well-matched pair. Even though it was still three years in the future, her mother began planning the wedding.

When September came again, James returned to New York and Eolene returned to Chowan. She once again threw herself into her studies, but soon something was wrong. Early in October, she began to feel ill. She developed a fever, and it was soon clear that her condition was serious. She took to her bed in the middle of the month, and while her friends around her hoped for her recovery, Eolene herself feared the worst. In the last week of October, as she lay in bed, she asked for James to be sent for from New York.

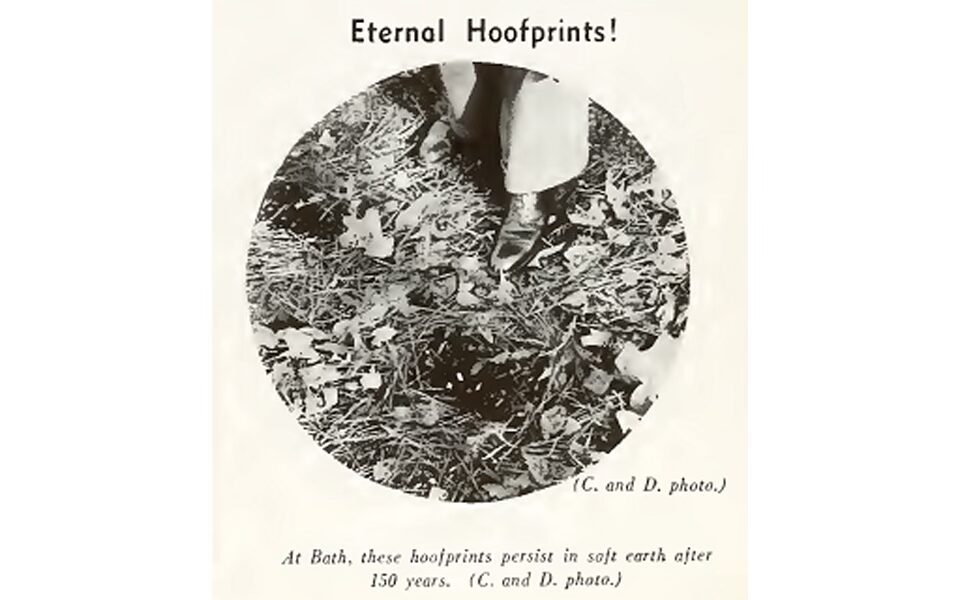

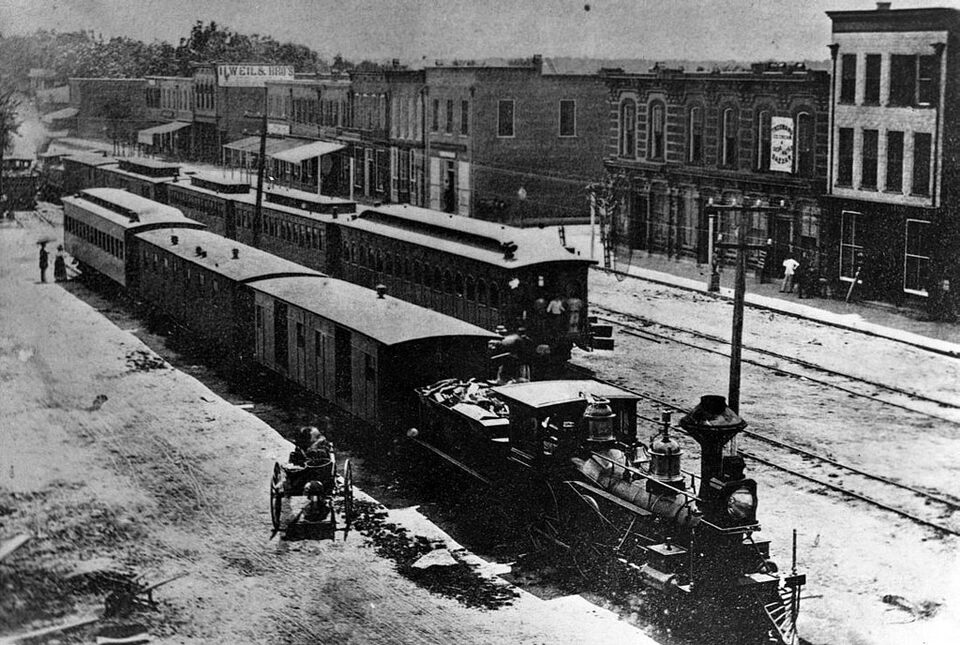

When James received the telegram, he immediately boarded the next train headed South. There were no direct lines from New York to this rural part of the state, and so he spend the next few days anxiously moving from line to line, station to station, only occasionally sleeping fitfully in his seat as the train rumbled on. When his last train pulled in to the small station at Seabord, he hired a horse and rode all night to Murfreesboro, arriving at dawn on the morning of November First.

But it was too late. Eolene had died the night before, on Halloween.

The school fell into mourning for the beloved Lady in Brown. James was heartbroken, and after the funeral he returned to New York and to his legal career. He never married.

But the next Halloween night, the students heard a strange sound in the halls of Chowan. It was the sound of rustling silk, moving through the hallways, just like the sound that the brown silk dresses Eolene always wore had made.

The next year, the sound returned. And the year after that. The legend soon grew that every year on Halloween, Eolene’s spirit would walk the halls. Some say that it was her spirit still waiting for her fiancee to arrive. Some say that once her spirit left her body, she quietly got up and resumed her studies.

In the century that’s passed since Eolene’s death, the Brown Lady has become a beloved part of Chowan tradition. Every year, the Brown Lady’s return is greeted with a vigil from the Chowan students and members of the town, when on Halloween night people gather in the dormitory to listen for the sound of the brown silk rustling through the hallways.