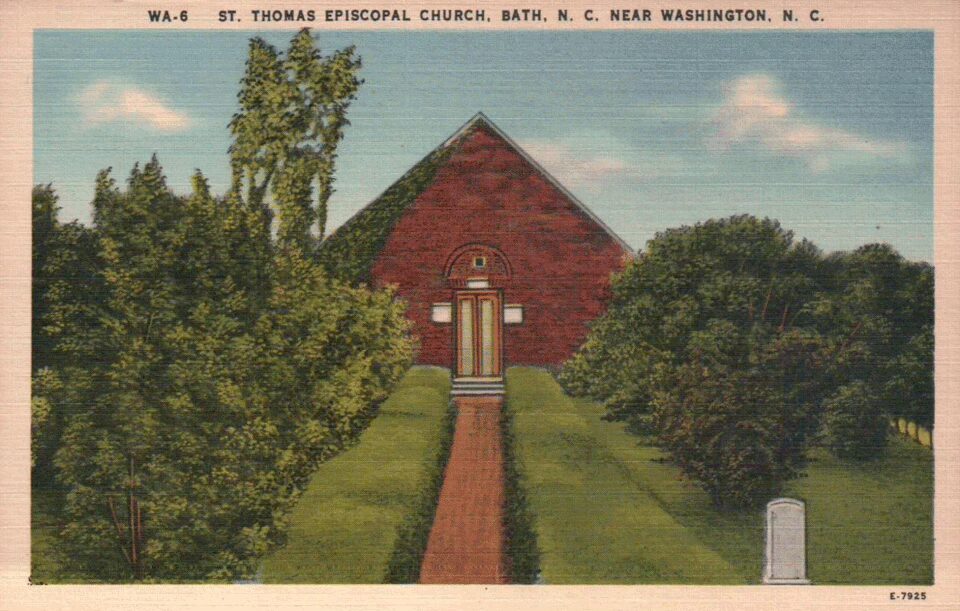

Bath town sits on the mouth of the Pamlico River. In the Eighteenth Century, Bath was an important port for the Carolina colonies. Ships traveling across the Atlantic Community would stop there, selling, resupplying, and trading. And not all of this traffic was legitimate. Bath was a favored haunt of pirates. The pirates appreciated Bath Town’s habit of not asking too many questions about where a cargo came from. It was also very conveniently located with easy access to both the open sea and the mazes of inlets and hidden coves that shape the North Carolina coastline. This gave those with reason to hide many routes to quietly sail off into when the British Navy showed up. The most famous of North Carolina’s pirates, Blackbeard himself, is said to have had a house and a wife or two in the town.

With all of this money pouring into the town, Bath soon developed a reputation as a freewheeling, easygoing kind of place. Liquor flowed freely, parties lasted all night long, and there was a good time easily had by anyone who wanted it.

But, as is the way with these things, inevitably someone shows up who not only doesn’t want a good time, but who doesn’t want anyone else to have one, either.

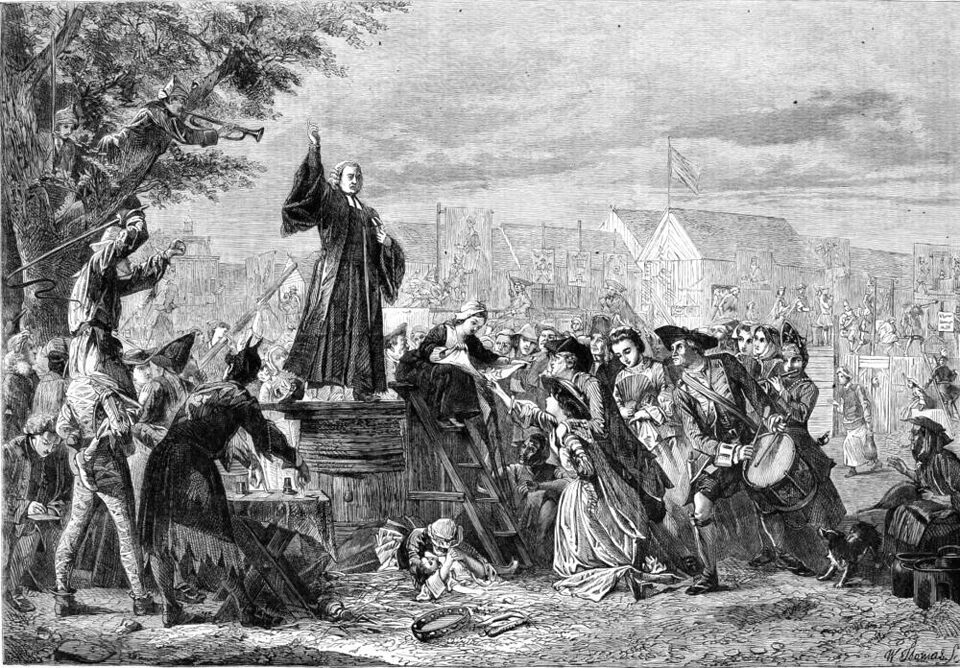

The traveling evangelist George Whitefield was one of the first celebrities in the American colonies. This staunch, cross-eyed, strictly Calvinist evangelist was reputed to have a voice that would carry for five miles. He used that voice to preach a grim vision of hellfire and damnation all up and down the American Colonies.

Whitefield was one of the prime movers of the wave of religious fervor that swept the American Colonies just before the Revolution. His sermons and the passion they inspired came to be known as “The Great Awakening,” and those who were generally concerned with just getting on and enjoying life instead of worrying so much about hellfire and damnation were a particular target of his.

Like many of these preachers to this day, Whitefield was also a showman. One of Whitefield’s pieces of evangelical stagecraft was to always travel in a wagon in which he carried his own coffin. Whitefield used the coffin to illustrate that he was prepared for death and confident in his own salvation. To drive the point even further home, Whitefield always slept in that coffin.

When he heard about the fun going on in Bath, of course it made his list. Needless to say, a strange, cross-eyed preacher who slept in a coffin and shouted about eternal damnation was not a welcome presence in a town that had come to accept the idea that doing what you wanted, when you wanted, was actually a pretty good way to go through life.

When Whitefield visited Bath, he was met by a delegation of locals who suggested that he might just want to turn around and head back the way he came. They may even have suggested that should he choose to stick around, he’d have an opportunity to put that coffin he was so fond of dragging around with him to its proper use.

Whitefield took the hint. But he couldn’t leave without at least making some kind of show. Whitefield climbed back on his wagon, took off his shoe and waved it at the assembled crowd, and proceeded to place a curse on the town.

“If a place won’t listen to The Word,” Whitefield said, “You shake the dust of the town off your feet, and the town shall be cursed. I have put a curse on this town for a hundred years.”

Shortly thereafter, the nearby town of Washington and its larger and more easily accessible port began to suck away Bath’s prosperity. The money stopped rolling in and the good times came to an end with them. By the middle of the Nineteenth Century, Bath had dwindled to a small, sleepy backwater, the same quiet little hamlet that’s there today. Whitefield took this as evidence that his curse had had an effect, and smugly spread the story of how he had brought down the town.