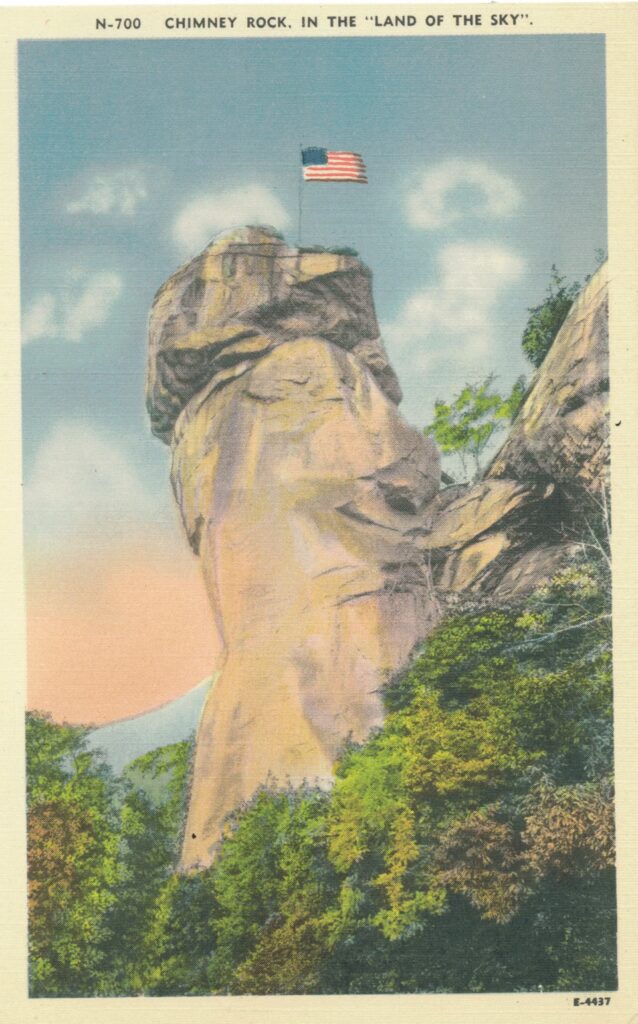

In the late 19th Century, the youngest son of an African-American farming family encountered a strange creature lurking in the Appalachian foothills. As a child, Alex White lived in the hills of Polk County near Lynn, tucked down in the Southwest corner of the state right on the South Carolina border. In the 1930s, Mr. White told a folklorist working with the Federal Writer’s Project about the hairy beast that lurked near his family’s farm, the thing he knew as the Whang Doodle.

According to Mr. White, he first heard of the Whang Doodle when he was very young, sitting by the fire in his family’s home. He remembered his mother was using a hot needle to burn out the cores of fig stems to make pipestems. He watched with fascination as his mother set a darning needle in the coals of the fire, letting it get red-hot before poking it into the stem and burning out the soft center. He recalled the sweet smell and thin smoke of the burning fig wood filling the room.

As his father watched the needle glowing red-hot in the fire, he said that the needle looked just like the Whang Doodle’s tongue.

His wife scolded him, telling him not to scare the children with stories of the Whang Doodle. The father got a mischievous look in his eye, and leaned back in his chair and started singing a song.

Whang Doodle holler, and Whang Doodle squall

Look out chillun, do he git you all

And with that, she told him to hush and took the children off to bed.

Now, the room were Alex and his younger brother Jim slept was also the room where his mother kept strings of peppers hanging from the ceiling to dry. As the wind blew and the light from the windows shone in, the shaking peppers cast shadows like long claws scratching on the walls. And Jim whispered that he, too, had heard about the Whang Doodle. And he quietly sung another verse of the song.

The Whang Doodle moaneth

And the Doodle Bug whineth

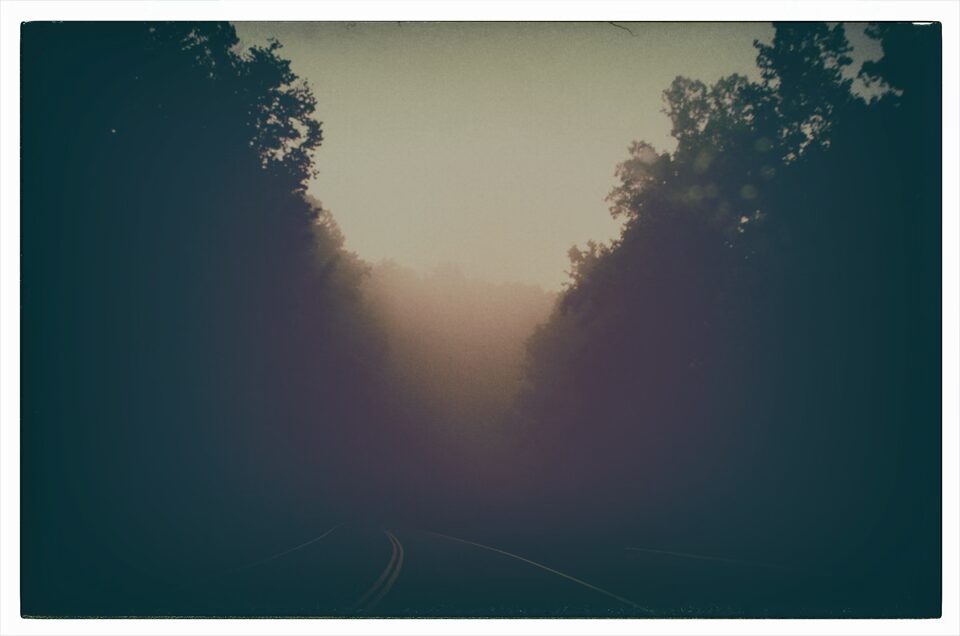

Hearing that, Alex was too scared to sleep. He lay awake listening to the sound of his parents snoring in the next room. To the sound o the dog scratching and shuffling beneath the house. To the thousand small sounds that fill up a country night. And as he lay awake, he heard a new, strange sound joining in. A long scream coming from way off in the night.

Ye-e-e-ow-ow-ow!

And Alex knew he wouldn’t sleep at all that night. He lay there, listening to the breeze in the trees, the crickets chirping, and the mice scuttling along in the walls. It seemed like it was all settling down again. But then, he heard that scream once more, and this time it was much, much closer.

Ye-e-e-ow-ow-ow!

And then the pig in the pen started howling and squealing. This woke the whole family up, and as his father yelled “Something is after the hog!” Alex’s father grabbed his gun, his mother grabbed a lantern, and the whole family rushed outdoors.

The light from the lantern swung around onto the pigpen. And there it caught the gleam of two huge eyes, glowing like balls of green fire. His father let off a blast from his shotgun, and young Alex saw something leap over the fence of the pen. Something as long as a cow, as high as a goat, with big mule ears, and covered all over with grey fur. In one long jump it was back in the woods, and as it went, it let out a scream.

Ye-e-e-ow-ow-ow!

And his father yelled, “God almighty boy, run for the house! Yonder goes the Whang Doodle!”

That was enough for Alex. He ran back inside and found that Jim had already beat him to their bedroom and had his head buried under the covers. And nobody in the house slept at all that night.

Alex White never saw the Whang Doodle again. But all his life, he was cautious about going deep into the woods, and would walk away whenever someone mentioned the Whang Doodle. And he never, ever forgot that song.

Whang Doodle holler, and Whang Doodle squall

Look out chillun, do he git you all

About This Story

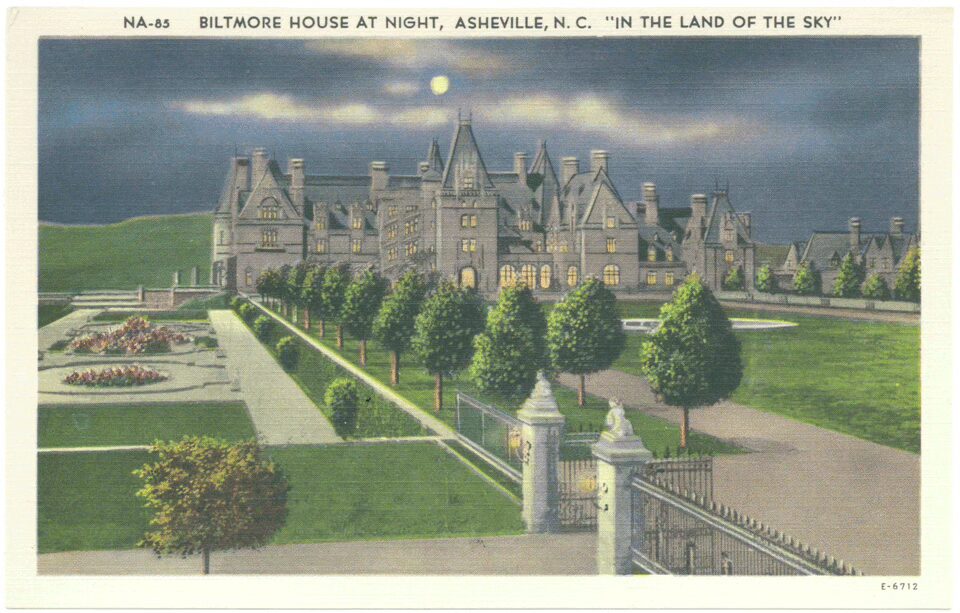

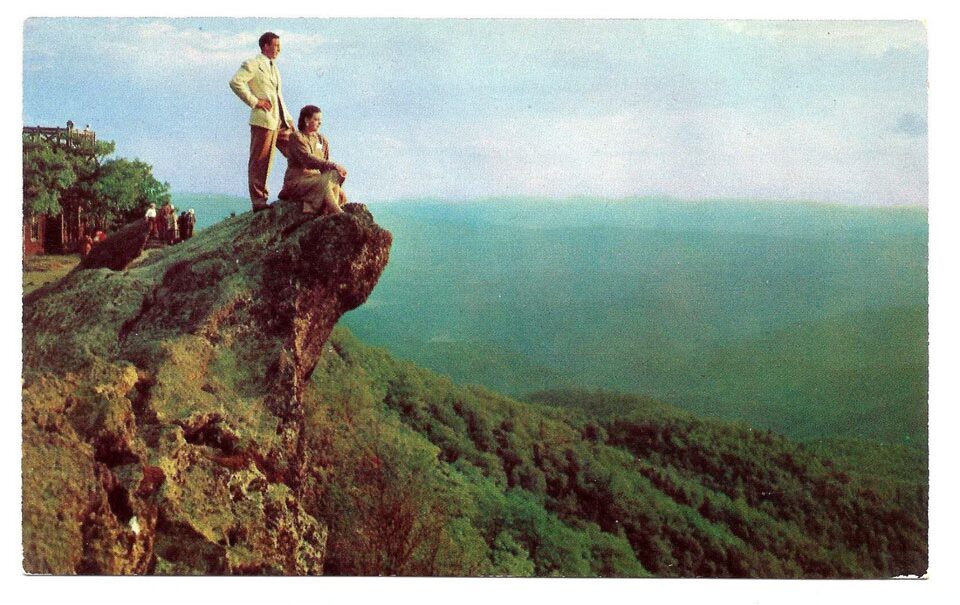

The Federal Writers’ Project was started in 1935 to provide employment to writers, historians, and librarians during the Great Depression. Originally designed to compose regional travel guides, the purpose of the project soon expanded to include recording folklore and the narratives of formerly enslaved African-Americans. Several of the stories collected in North Carolina were compiled into the book Bundle Of Troubles And Other Tarheel Tales, form which this story is adapted.

Alex White’s original tale was written down in dialect, an approximation of the colloquial speech and regional accent of African-Americans. This was a common practice at the time, but even in the internal workings of the Federal Writers’ Project, the practice was not uncontroversial. Many felt that using non-standard spellings and grammar perpetuated negative stereotypes. Others, including Zora Neale Hurston, who worked for the project, though that capturing the rhythms and intonation was important when trying to recreate the experience of oral narration in written form. She said this with the important clarification that this would only work if the author had a genuine understanding of the dialect and a good ear for recording it. Otherwise, what was written down would be just a caricature of the speech. Because we didn’t hear the sound of his voice as Mr. White told this wonderful story in person all those years ago, we don’t feel qualified to try to capture those rhythms, and have respectfully modified the tale into standard English, with the exception of the song verses, which are quoted directly as recorded.