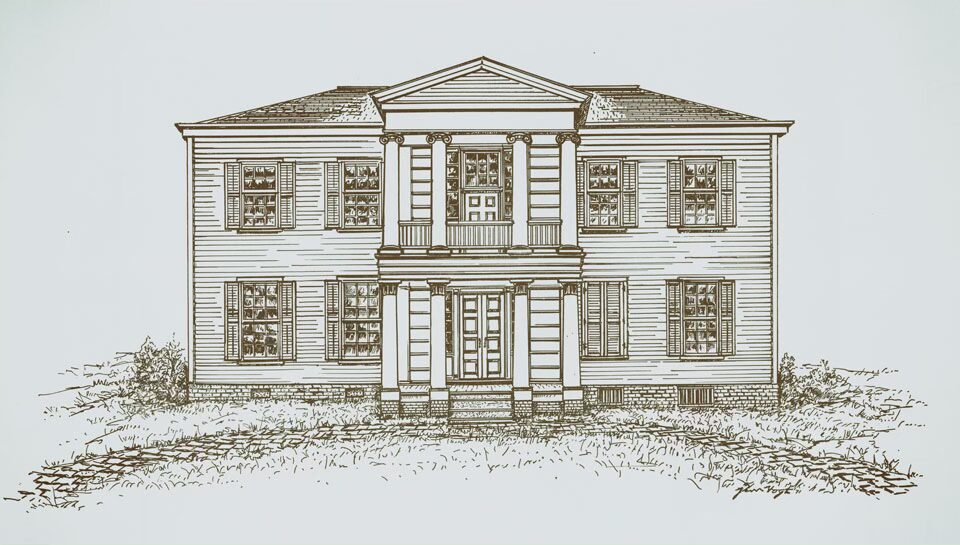

Mordecai House is one of Raleigh’s finest historic buildings. The original portion of the house dates from around 1785 and was built by Joel Lane for his son, Henry. Joel Lane was one of the instrumental figures in the establishment of Raleigh as the first planned state capitol in the US. The Capitol building and a substantial portion of downtown Raleigh all stand on what was once Lane’s Wakefield Plantation.

Why Raleigh was built where it was, instead of closer to the Neusse River and its access to transportation and the sea, has always been something of a historical puzzle. There’s a legend that Lane was the one behind the location. The story goes that Lane persuaded the Capitol planning committee to purchase a large chunk of his unwanted land during a night of very heavy drinking at a local tavern, with Lane picking up the tab.

Mordecai House acquired its name when Moses Mordecai married into the Lane family in 1817. Mordecai not only married into the Lane family, he married in to the family twice. When his first wife, Margaret Lane, died in 1824, he married her younger sister, Ann.

Moses Mordecai was a member of one of the most prominent and fascinating Ashkenazi Jewish Families in early American history. His father, Jacob Mordecai, was a progressive, intelligent leader who was the first director of the Female Seminary in Warrenton, North Carolina. This seminary provided an unusual multi-faith teaching environment for young ladies of the town. Moses Mordecai’s older sister, Rachel Mordecai Lazarus, was an extremely intellectually gifted woman whose correspondence with the best-selling novelist Maria Edgeworth persuaded the author to amend the anti-semitic prejudice that unfortunately permeated much of her early work. Rachel Mordecai Lazarus was an early feminist and an early voice in the call for what would become the Reform Movement in American Judaism.

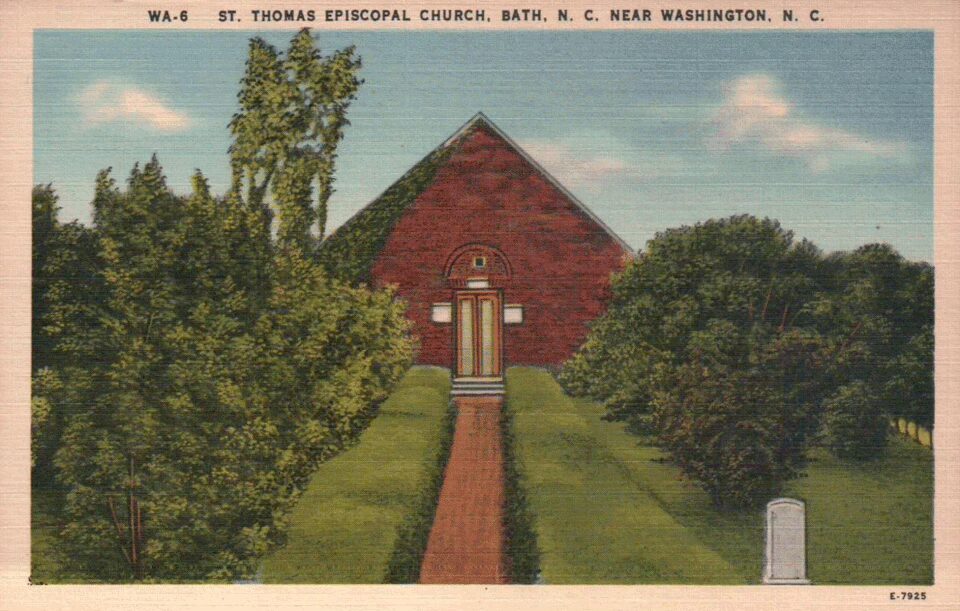

The Mordecai family’s story is a complex one of change and assimilation that many Jews faced when moving to America. While in this country they were ostensibly free to practice their faith and live as they chose, there was still constant pressure to lose their distinct identity in order to become “fully American”. Moses Mordecai apparently deferred to the wishes of his Episcopalian wives, as his branch of the family were thereafter Christian, and by the time Moses Mordecai’s granddaughter Elen Mordecai wrote her memoir Gleanings of Long Ago, the family’s Jewish origins were only a vague memory. But Moses’ son Henry did play an important role in Raleigh’s Jewish history, donating a portion of the Mordecai lands to found the first Jewish cemetery in Raleigh.

It was also sometime in Moses Mordecai’s lifetime that the pronunciation of the family name Mordecai shifted from the traditional long I ending to a long E. This unique pronunciation is still used for the name of the house to this day.

The descendants of Moses Mordecai inhabited the house for five more generations, until the house was willed to the city in 1964, and it’s now part of a public park.

The ghost that inhabits the house is said to be the spirit of Mary Willis Mordecai Turk, who lived from 1858 to 1937. She appears sporadically as an apparition in a grey Nineteenth Century dress. She can occasionally be heard playing the piano in the downstairs drawing room, and visitors to the house have occasionally seen a grey mist hovering near that piano.

Mordecai House was featured on an episode of the Sci-Fi Channel’s Ghost Hunters, where the band of supernatural investigators and sometime plumbers displayed their usual degree of scientific and intellectual rigor by completely confusing the house with the birthplace of President Andrew Johnson, also located in the park, and then all coming down with food poisoning.