Nowadays, it seems like the Appalachian trail is as crowded as a busy city street, with noisy novice hikers clad head to toe in the latest, most expensive, gear, armed with GPS devices and constantly talking on their cell phones. With the hills becoming so crowded, a man who wants to get out alone in the wilderness has farther and farther to go.

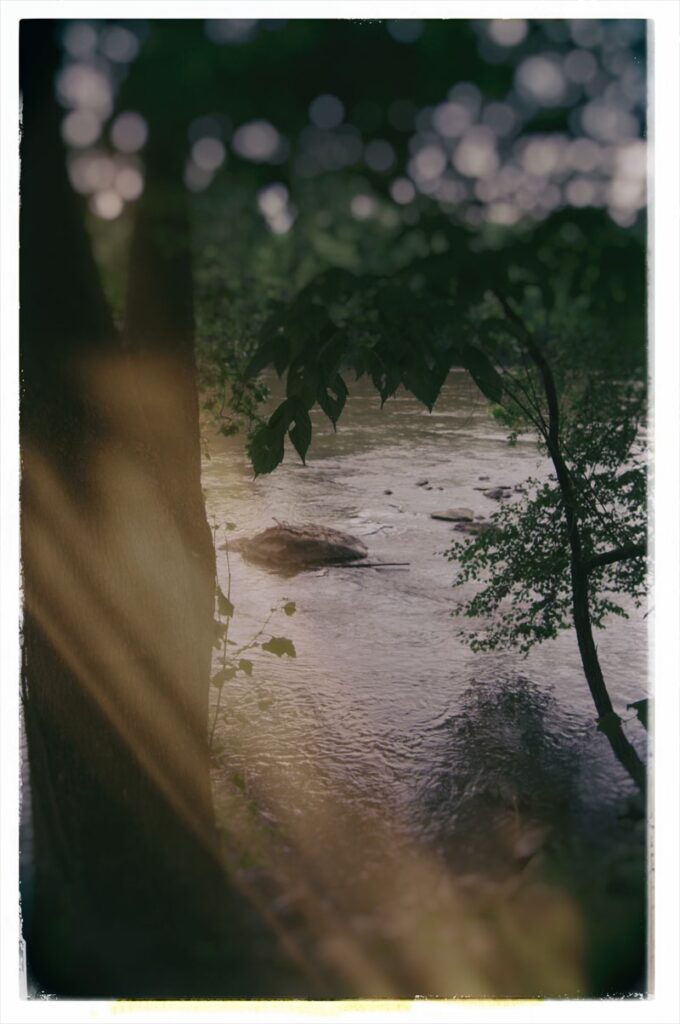

Such a man might decide to head out on his own, and just follow the course of a nearby wandering river. If he started out from Asheville, his course would naturally be along the French Broad whose wide banks skirt the city. Taking a light pack and a few days worth of food, he could just set out along the course of the river, pausing frequently to watch the water rolling over its rocks, and just enjoying the peacefulness and quiet still to be found on its banks.

But on the first night, after he pitches his tent and settles down in his sleeping bag, he may find himself tossing and turning and troubled by strange dreams. A beautiful, dark haired, dark eyed woman walks in and out of his restless mind all night. And though the whole night through he dreams of nothing but her, he can never see her clearly and she always seems like she’s a great distance away. He is woken before dawn by the sound of what he thinks is singing, but the sound soon vanishes as he waits in his tent for the light to come.

When dawn comes, he cooks his breakfast, packs his tent, and makes his way further down the river, moving more slowly than yesterday and still feeling groggy and dazed. He doesn’t get as far down the river as he thinks he will, and when the evening comes he’s glad to pitch his tent and lay down wrapped in his bag. There ge expects sleep to come easy after his exhausting day.

But again his dreams are troubled by the vision of the dark-haired woman. Again, he awakes to the sound of singing, but this time the voice comes at midnight, and the young man steps out of his tent to stand by the banks of the river in the darkness, the sound persists. A subtle, beautiful singing full of rich melancholy and precious longing. Enchanted, he lays down by the side of the river, and with the sound in his mind his exhausted body gives in and he drifts off to sleep. When he wakes on the hard rocks, it’s well past dawn and all he can remember from his dreams is that the woman was there again and this time she seemed much closer.

On the third day, he walks even more slowly than the last, and when he gets to a certain bend in the river where the water collects in a deep pool, he finds himself unwilling to move from the spot. He pitches his tent well before dusk and sits by the river to wait.

As twilight descends into night, the young man doesn’t go inside of his tent, but still sits by the side of the river, staring into the deep waters of the pool. As night comes into its own, the young man hears the sweet singing once again, more indescribably beautiful than any voice he has ever heard. And as the voice grows louder it seems to be coming from the pool of dark water by his feet. And as he looks into the pool, he seems to see the form of a beautiful dark-haired woman rising out of the water towards him. She is naked and more perfect than he could have imagined, the smooth curves of her body seeming to repeat the slow, smooth curves of the river. And he knows that she is singing to him.

Unable to resist, the young man reaches into the water to touch the woman, but as her hand wraps around his, it’s not warm flesh that he feels, but cold, rough and slimy scales and claws that dig painfully into his arm before he can pull away.

Before he even has a chance to scream, the cold grip pulls him into the dark water and he disappears below the surface and to his doom, another young life lost to the Siren of the French Broad.

A Little History of this Story

The story of the Siren of the French Broad first appears in print in 1845 as Tzelica, A Tradition of the French Broad, a 64-line poem by William Gilmore Simms published in his Southern and Western magazine, but is more widely known from the 1896 retelling in Charles Montgomery Skinner’s Myths and Legends of Our Own Land.

One of the most puzzling mysteries of the French Broad river itself is why exactly it is French. The name first appears in official records in 1777, and may come from the fact that with treaty of Paris that ended the French and Indian war in 1763 all waters that flowed into the Mississippi basin were deemed French territory. The French Broad flows west into the Tennessee river which eventually joins the Mississippi, and so the name might have been given around that time. There was also another nearby river that had been named the Broad River, so the French could have been added to help differentiate it from the nearby Broad river.

Skinner reports that the Cherokee name for the river was Tselica, though this may be more a product of Skinner’s imagination than the Cherokee language. Cherokee naming conventions also differed from European ones, along with eastern Native American naming conventions in general, in that the Native Americans tended not to give single names to entire rivers but instead gave individual names to geographically important features along the river. This approach certainly makes more sense if you’re traveling along a river instead of looking at it on a map, but it was the source of miscommunication between the Europeans conducting their surveys and the Indians being asked the questions. The Europeans thought they were asking the name of the whole river, while the Indians were usually giving the name of the most convenient feature. In this way, the names of many smaller features transferred themselves onto entire rivers. The not-too distant Hiwassee river derives its name from a Cherokee word meaning “Stone Wall” for a landmark perhaps built by the The Moon-Eyed People.

The U.S. Board on Geographic names has recorded several different names for the French Broad, including Poelico, Satica, and Tahkeeoskee, all of of which may be features on the river whose identify is forever lost. Still, the name as we have it is a fine one, and reminds us of what seems like an improbable time when part of North Carolina was French territory.