In the mountains of the Southern Appalachians, from North Carolina down through Georgia and Alabama, the remains of ancient stone structures line the ridges. Some of these are additions to natural rock formations, others are entirely man-made. Who built these structures? Are they the remains of an ancient war fought in the Appalachians? Are they all that’s left of the Moon-Eyed People?

The Moon-Eyed People are a race of small men who, according to Cherokee legend, once lived in the Southern Appalachians. The Moon-Eyed People were said to being physically very different from the Cherokee, being bearded and having pale, perfectly white skin. They were called Moon-Eyed because they were unable to see in daylight, their sensitive eyes being blinded by the sun. For this reason, they were strictly nocturnal, and lived in underground caverns.

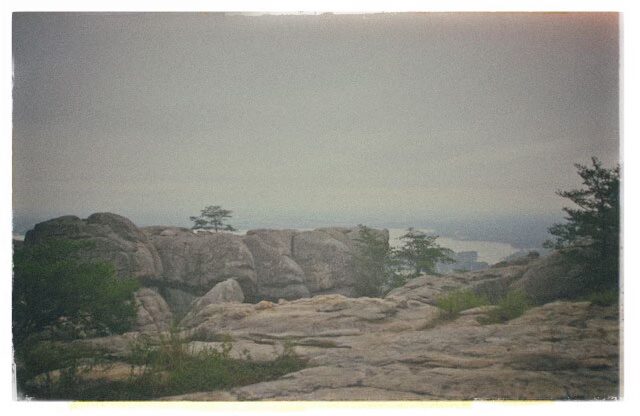

Perhaps the most famous structure associated with The Moon-Eyed People is just over the North Carolina border in Georgia at Fort Mountain. Now a state park, Fort Mountain gets its name form the 850 foot long stone wall that varies in height from two to six feet and stretches along the top of the ridge. This stone wall is thought to have been constructed around 400 – 500 C.E.

According to one Cherokee legend, this wall is a remnant of a war that the Moon-Eyed people fought and lost against the neighboring Creek nation. The Creeks drove the Moon-Eyed People from their homeland during a full moon, which even the pale light of is blinding to these nocturnal people.

Another version of the story has is that it was the Cherokee themselves who waged war against the Moon-Eyed People, driving them from their home at Hiwassee, a village near what is now Murphy, North Carolina, west into Tennessee. Both versions of the story say the Moon-Eyed People began living underground after losing the war.

Cherokee cosmology is complex and fascinating, and describes a universe where humans share the world with other, non-human, supernatural peoples. In the traditional Cherokee concept of the world, races such as the Nunnehi or the Yunwi Tsudi are a part of the natural world who interact with humans at their own discretion, similar to the traditional idea of fairies in the British Isles. However, what’s interesting is that The Moon-Eyed People are never described as being supernatural, but are remembered as another group of humans who were physically very different than the Native Americans.

Because the description of the Moon-Eyed People is that they are pale-skinned and bearded, this has led to some amount of speculation, quite a bit of it wild, that the legend of the Moon-Eyed People represents a Cherokee folk memory of contact with a group of European settlers who made it to the new world before Columbus. Particularly, the Cherokee legend of the Moon-Eyed People has been matched up with the Welsh legend of Prince Madoc.

Acording to the Welsh story, Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd was a Welsh prince who, disenchanted with the civil war wracking his homeland, set sail with his brother Rhirid and a few followers in 1170 across the Atlantic Ocean and landed somewhere around Mobile Bay, Alabama. After some exploring up and down the rivers of southern America, Madoc decided he liked the place well enough and decided to move in. Leaving Rhirid and some of his fellow Welshmen behind, Madoc returned to his native country and recruited enough followers to fill ten ships. He and his colonists set sail back to America and was never heard from in Wales again. Some have speculated that the Moon-Eyed People are the descendants of Madoc’s colonists, and that it was these Welshman who fought a war with the Cherokee, and these Welshmen who built the stone forts that dot the ridges of the mountains.

Driven out by the Cherokee, Madoc’s descendants found their way South to Florida and Alabama, where they continued to live in, slowly absorbing bits of Native American culture, until they became a strange tribe of pale Indians, living and dressing in Native ways but speaking Welsh.

More About this Story

There is absolutely no historical or archaeological evidence to support the tale of Prince Madoc. King Owain Gwynedd was a real enough historical figure, but no contemporary source names either a Madoc or a Rhirid as his son. The story of Madoc’s journey seems to have arisen around 1580 as a piece of propaganda to bolster England’s claim to the new world, which needed some bolstering because at that time England’s arch-rival Spain was doing most of the actual colonization in the Americas. Spreading the idea that someone from the British Isles had gotten there first painted the Spanish as Johnny-Come-Lately’s usurping the rightful English claim to the Americas. Of course, the legitimacy of either claim would have been very correctly questioned by the vast number of people who happened to be living in the “New” World at the time.

Stories of European settlers who encountered Welsh-speaking Indians began circulating in the late 17th Century. A Reverend Morgan Jones claimed to have been captured by a people called the Doeg in present-day South Carolina in 1666, who he was astonished to learn spoke Welsh. According to Jones’ account, he preached Christianity to the Doeg for a few months before being set free. Amazingly, Jones seems not to have told anyone of this interesting experience until twenty years after it happened.

Another story tells of a Welsh sailor named Steadman, who was shipwrecked somewhere on the Gulf Coast of Alabama or Florida in in the 1660s, and was astonished to discover a group of Welsh-speaking Natives. Steadman’s account failed to be published until 1777, and its authenticity is somewhat suspect.

In the 18th and 19th centuries these stories of Welsh Indians were extremely popular. Govenor Robert Dinwidde of Virginia even put forth the staggering sum of £500 to finance an expedition to find the Welsh Indians he believed to be west of the Mississippi. Lewis and Clark even kept an eye out for the Welsh Indians on their famous expedition.

This idea of Welsh Indians persisted long enough that, for a good part of the twentieth century, a historical maker commemorating Prince Madoc’s journey and donated by the Daughters of the American Revolution stood on the beach in Mobile bay until it was removed by a more historically conscientious member of the park service.

When James Mooney published Myths and Legends of the Cherokee in 1902 and introduced the Cherokee legend of the Moon-Eyed People to a larger audience seems to be when the Cherokee story and the story of Prince Madoc began to be conflated.

The idea of Welsh Indians was just one of several popular ideas of pre-Columbian contact with the New World that were circulating in America at the time. The notion that the Lost Tribes of Israel somehow also managed to find their way to North America even found its way into the first new American religion when Joseph Smith published The Book of Mormon.

Many of these stories seem to have risen up from the concept that the citizens of the new American nation had of Native Americans, as opposed to the historical reality of the continent. The romantic idea of Indians as primordial, timeless, and having lived in essentially the same manner for centuries before European contact began to be prevalent in America as the new nation emerged. Ideas about the pre-contact size of the population of America at the time were also grossly underestimated. Americans saw the Indians as being scattered in small populations, unaware that these were the remnants of once populous nations whose ranks had been devastated by European diseases in the early years of contact. Modern estimates say as much as 90% of the native population of North America may have died from disease in the 16th and 17 centuries.

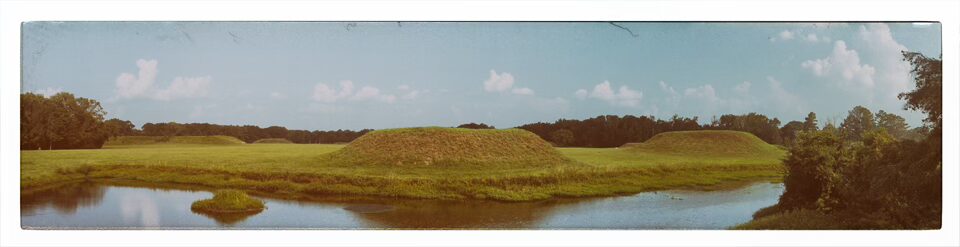

These civilizations left behind physical remains which Europeans encountered. Particularly, the mound-building Cahokian culture left behind the remains of cities and temple complexes across the Southeastern United States along the Mississippi valley, stretching as far east as Town Creek Mound in North Carolina.

At its height around 1200, the city called Cahokia near modern St. Louis was twice the size of contemporary London, and larger than any other city in North America would be again until the 20th century. Encounters with the abundant evidence of this civilization led to wild speculation about who built the mounds and what their purpose was.

Unable to reconcile the physical evidence with their perceptions of the Native Americans, combined with the insidious assumptions of European superiority in all things, wildly speculative ideas about ancient European visitors rose up to fill the gaps. But, except for a brief period of Viking contact in the 10th and 11th Centuries, there is no evidence that such contact ever happened, and quite a bit of evidence that it didn’t happen.

So the hill forts that stretch across the Southern Appalachians, and the Cherokee legend of a conflict with some other people, may very well be related. It could all be evidence of a war that was fought on an impressive scale on North American soil a very long time ago. We may never know the parties involved in the conflict, but we can be fairly certain that none of them were Welsh.