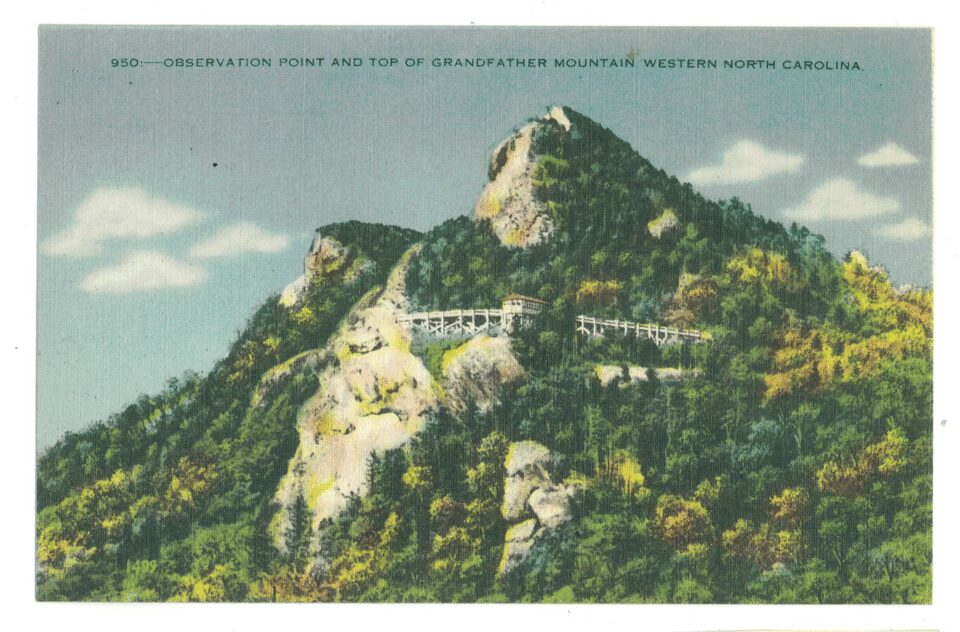

Grandfather Mountain sands above Blowing Rock Highway near Linville. The mountain gets its name from the mountain’s profile, which resembles the head of a bearded old man laying down in sleep. The unique and gorgeous natural environment around Grandfather has long been a draw for visitors to the North Carolina mountains. Grandfather Mountain was operated as a private tourist attraction for many years until 2011, when it was purchased by the State of North Carolina and is now a publicly-owned nature preserve.

The mountain has been a source of inspiration to many, including Shepherd M. Dugger, who praises its beauty in extremely flowery language in his highly odd combination of historical romance and travel guide The Balsam Groves of Grandfather Mountain. Originally published in 1907, Dugger’s book often cited as some of the finest bad writing ever produced by a North Carolina author. But as bad as his prose may be, Dugger is not alone in finding beauty in the woods and trails of grandfather mountain.

Hiking is one of the prime attractions that brings people to the park. The park’s eleven trails cover miles of terrain, and the more difficut backcountry trails take hikers through unique ecosystems that are home to dozens of rare and endangered species. It’s on one of these trails that something even more rare has been seen, the ghost of a lost hiker.

The phantom hiker of Grandfather Mountain is said to be an older man, bearded, with a rough and grizzled appearance. He can be distinguished from a living hiker by the lack of Neoprene and Gore-Tex in his wardrobe. Instead, he’s said to wear old-fashioned workman’s clothes that look like they’re from somewhere in the middle of the Twentieth Century. He wears a rough canvas army backpack and carries a long walking stick.

The phantom hiker is said to appear mostly as the evening is settling in, when most of the day hikers have left or are working their way back. He never says anything, and will never acknowledge any greeting. He simply appears walking along one of the trails in the backcountry, moves swiftly ahead of anyone else he encounters, and then simply vanishes.

No one knows who this mysterious figure is. Some have suggested that he was a hiker who became lost in the the thick woods around the mountain, and fell or was injured and was unable to make his way back out. Others have said he’s just the spirit of a man who loved the mountain so much that he chose to stay there after he died.

This ghostly hiker seems to do no harm. He seems to want little to do with people in general. He only seems to be there, like all the other visitors, to enjoy the natural wonder of Grandfather Mountain.