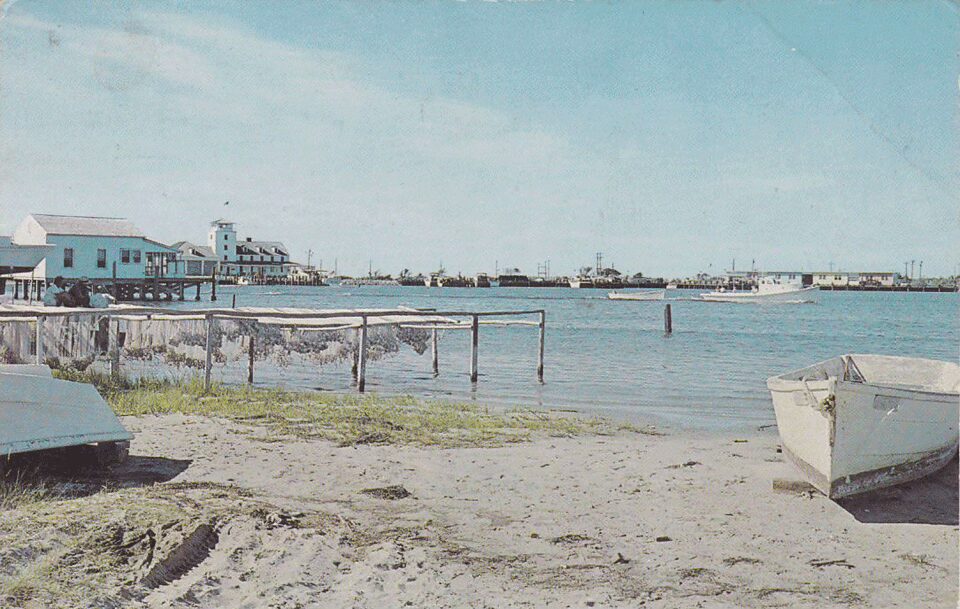

It’s said that on the night of the new moon each September, a strange and ghastly sight can be seen off of Ocracoke Island. There in the waters off the Outer Banks, each year on that one night, a phantom ship engulfed in flames floats silently by the island and disappears into the night. How this came to be takes us back to the early days of the North Carolina colony, to days of settlers and pirates, and to the reign of Queen Anne.

In the late Seventeenth and early Eighteenth Centuries, the religious wars that ravaged Europe caused mass migrations of people displaced by the conflicts. In these wars England was allied to the Palatine States, in what is today Germany and Switzerland. The countries shared a Protestant faith and a complex history of marriage bonds. In 1689, when the unpopular James II was forced to abdicate by Parliament, James’ daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange were brought in to replace the exiled monarch. Suddenly having a German king on the throne drastically shifted many of England’s diplomatic alliances, and William was happy to use the very large army he suddenly found at his disposal to continue and expand the wars that he had already been fighting in back in the Palatinate Sates.

These wars produced refugees, and William and Mary opened England’s doors to thousands of them. England soon found itself housing a large population German-Speaking refugees who had fled from the continent. These refugees were not ordinary peasants, but well-to-do skilled craftsmen and trade workers. This influx continued for years, into the reign of Queen Anne. The presence of so much unemployed skilled labor dealt a massive blow to the English economy. Native English craftsmen found they were facing levels of competition they’d never before known, and the price for skilled labor plummeted. So the question of what to do with all these Palatines became pressing on Parliament.

A swiss baron, Cristoph von Graffnreid, offered a solution. With the Crown’s permission, he would escort a large number of these refugees to a settlement in the Carolina colonies, to be called New Berne. The plan was met with delight, and the transportation of the Palatine colonists soon began.

It was on one of these voyages that the captain of the chartered vessel, an unscrupulous and greedy man, noticed that his passengers were carrying an unusual amount of gold, jewels, and other wealth with them. Whatever family treasures the Palatines had managed to get out of their homelands were now being taken to the New World. Eyeing this wealth, the greedy captain hatched a plan.

As the ship drew closer to the American coast and the Outer Banks were in sight, on a moonless night the captain put that plan into action. He enlisted the help of his equally greedy crew. One night, the crew crept below decks and, one by one, slit the throat of every passenger on board as they slept. The crew then loaded the passenger’s treasure on the ship’s long boat.

To cover up the crime, the men doused the decks with oil and set the ship on fire as they dropped the long boat into the ocean and set out for the pirate’s refuge at Bath. As the men set off in the long boat, the ship they left behind became engulfed in flames.

As the captain and his men gleefully rowed the long boat away from the flaming ship, they laughed and bragged to each other about their deed. But then the captain looked back towards the flaming ship, and what he saw shocked him. Though the sails were down and the night was still the ship was moving. It was plowing through the waters at high speed, as though it was at full sail and being steered by human hands. But they knew there was not a living soul on board. They had killed everyone on board. This flaming ship filled with dead men was sailing right towards them.

Panicked, the crew rowed fiercely trying to avoid the oncoming ship, but it was no use. The flaming ship rammed the longboat, sinking it, the treasure, and the murderers beneath the waves. The next day, the burned husk of the ship washed ashore on Ocracoke.

Each year, this strangle spectacle is reenacted off the coast of Ocracoke. If you look into the waters off of the Northeast corner of the island on that night in September, you might see it, too.