On August 27, 1587 Governor John White sailed from the newly-founded English colony on Roanoke Island to return across the sea for supplies. He left behind the first settlement in the new English colony of Virginia, consisting of eighty-nine men, seventeen women, and eleven children. One of those children was his own granddaughter, the first English child to be born in the New World — Virginia Dare. None of these colonists were ever seen by English eyes again.

White had intended to return to the Roanoke colony the next year, but the threat of Spanish invasion from the great Armada of 1588 and the constantly-shifting politics of the Elizabethan court delayed White’s return until 1590. When he arrived, he found the colony abandoned, the only clue to the fate of the colonists being the word CROATOAN carved into a tree. This was the name of a nearby island, the home of the english-speaking Croatan Indian Manteo. Manteo and another Croatan, Wanchese, had met the 1584 reconnaissance expedition for the colony. These two men had left their home in the Outer Banks and journeyed with that expedition on its return to England. The men had learned English on their journey. When they returned with a later expedition, they were positioned at the colonists arrival to be key negotiators between the inhabitants of the island and the newcomers.

White was desperate to follow up on the clue carved into the tree. But he was prevented from making a thorough search of the islands. His ship was threatened by a large oncoming storm, and the captain was eager both to escape that danger and to turn south and hunt for Spanish treasure ships. White was forced to sail on, not knowing what had become of his family and the other settlers. By the time of the next attempt at Colonization in 1608 at Jamestown, the fate of the Lost Colonists had already become the stuff of legend.

One of these legends that has been told time and again on the North Carolina Outer Banks follows the sad, strange fate of that first English child born on New World soil.

According to the legend, Wanchese was fearful of the threat posed by the Englishmen and plotted with a nearby tribe to lead a sneak attack against the colonists. Fleeing for their lives, the colonists were gathered together by Manteo to escape and join his tribe. It was Elanor Dare, the mother of Virginia, who had the foresight to carve their destination in a tree, which she did with her husband lying dead of an arrow at her feet and her precious child clutched into her arms.

But a good number of the colonists did escape, and they lived peacefully with the Croatan Indians. Young Virginia Dare grew to be a beautiful maiden, whose natural grace and virtue made her an example to all who knew her, colonists and Indians alike. As she became a young woman, she naturally attracted the attentions of suitors. Among these young men were the noble Okisko, and a jealous sorcerer named Chico.

Chico was the first to offer his hand to the young Virginia Dare, but the maiden refused his advances. Enraged, he used his dark arts to curse the girl, and transformed her body into that of a snow-white deer.

The mysterious white doe was often seen on Roanoke, sadly walking through the now-overgrown and decaying houses built by her people. The story of this beautiful, elusive creature soon spread to all the tribes on the islands.

Okisko, Virginia Dare’s other suitor, figured that this white doe had shown up about the same time Virginia Dare had gone missing. Reckoning that his rival in love was skilled at the dark arts, it didn’t take him long to figure out that this white doe was his own beloved. Seeking the help of a friendly sorcerer, he learned how to make a magic arrowhead from the mother-of-pearl lining of an oyster shell that would undo the curse.

But Wanchese had also heard of the white doe and, not knowing that it was the cursed English girl, he vowed to kill the rare creature in a bid to prove his worth as a warrior. To this end, he pledged to use a silver arrowhead given to him by Queen Elizabeth when he had been in England.

Okisko and Wanchese, unknown to one another, both tracked the white doe for weeks — one pledged to return her to her true form, the other sworn to bring her death. And as it happened, they came upon the deer at the same hour of the same day, as the delicate creature was drinking from a deep pool in the forest. Okisko saw his beloved, Wanchese saw his prey, and at the same time they both released their arrows. Both their arrows hit the heart of the white deer in a single moment, Okisko’s undoing the enchantment and Wanchese’s bringing death.

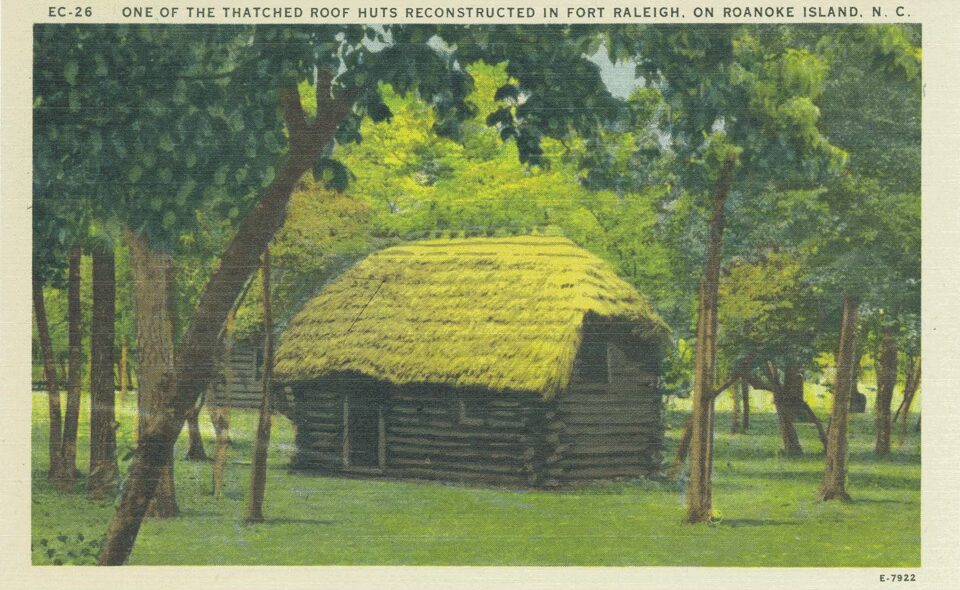

Seeing what he had done, Wanchese fled the island in fear, but Okisko sadly carried the body of his beloved to the old fort built by the colonists and buried her at its center.

But soon by that pool where Virginia Dare died, a new vine sprung up, whose grapes were sweeter than any that anyone had tasted before, but whose juice was a red as blood. This was the scuppernong, the grape from which the first North Carolina wines were made.

And those grapes are why there’s much more to this story than the story. Learn the scary truth behind the story of Virginia Dare.

More About This Story

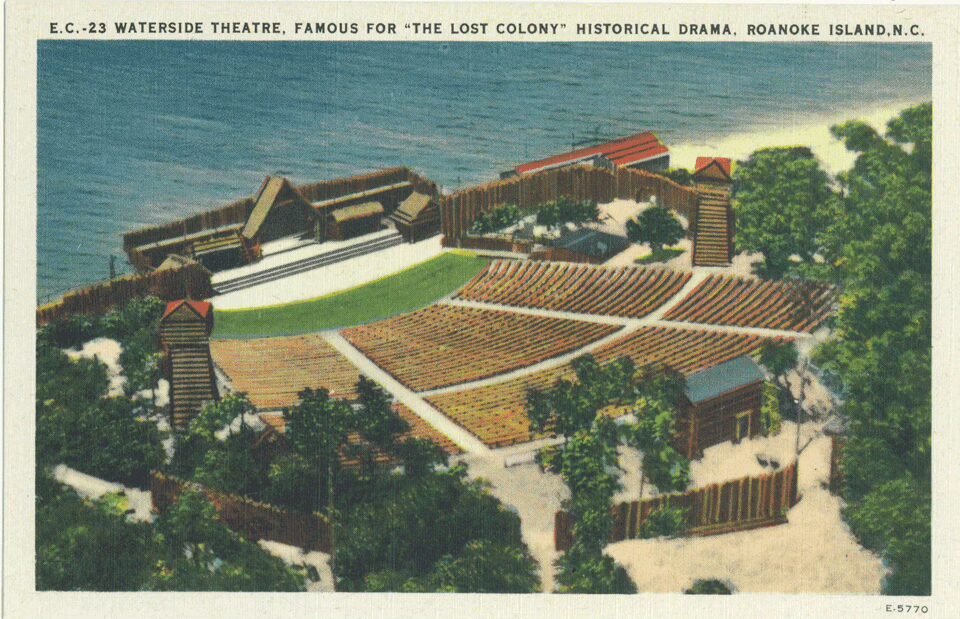

While the exact fate of the Lost Colony is unknown, most historians agree that the chances of Virginia Dare having been transformed into a deer are vanishingly small. But the legend of Virginia Dare does represent a unique combination of a literary tradition that was imported to the New World from England, along with some unquestionably American advertising showmanship.

The story of Virginia Dare’s transformation into a deer seems to have been first told in the late 19th Century. The earliest versions of the story, such as the one recorded in an 1880 travel article in the New York Times, leave out the grapes and even the Indians entirely. In these versions, Virginia Dare is a deer with a remarkably long lifespan, and is eventually brought down by a silver bullet shot form a Virginia hunter’s rifle in the 19th Century.

But these first versions of the story are already drawing from an established literary tradition. The White deer is a common motif in English literary legends and is often used as a symbol of Christian virtue. A similar story of a young girl transformed into a white deer can be found in Yorkshire, where it formed the basis for Wordsworth’s poem The White Deer of Rylstone.

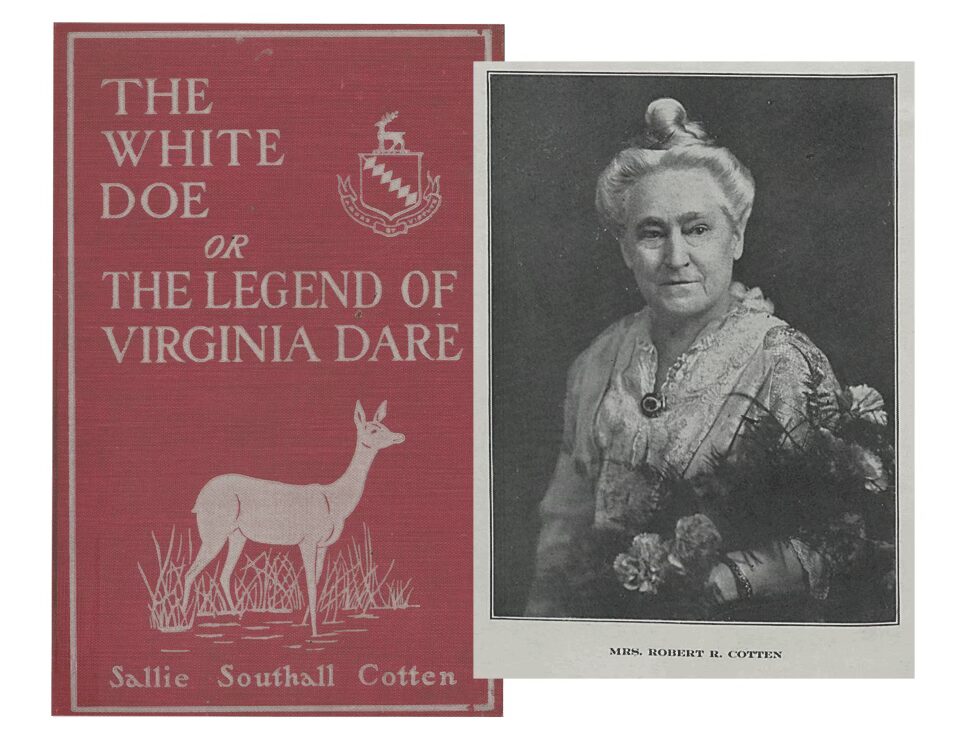

The author of the most famous version of the Virginia Dare story was certainly aware of this tradition. This is the version of the story whose summary you’ve just read, and which comes from Sallie Southall Cotten’s 1901 book-length poem The White Doe, or the Fate of Virginia Dare.

Sallie Southall Cotten was a remarkable woman, a strong promoter of women’s rights and a leader in the women’s club movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An organizer of the North Carolina exhibition at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, it was she who commissioned the beautifully carved Virginia Dare desk that illustrates scenes from the legend and is now on display at the Lost Colony Museum in Roanoke Festival Park.

Cotten was also an early advocate of North Carolina’s wine industry, and the addition of the scuppernong grapes colored by Virginia Dare’s blood was her contribution to the legend. This was probably because The White Doe was written to sell scuppernong wine.

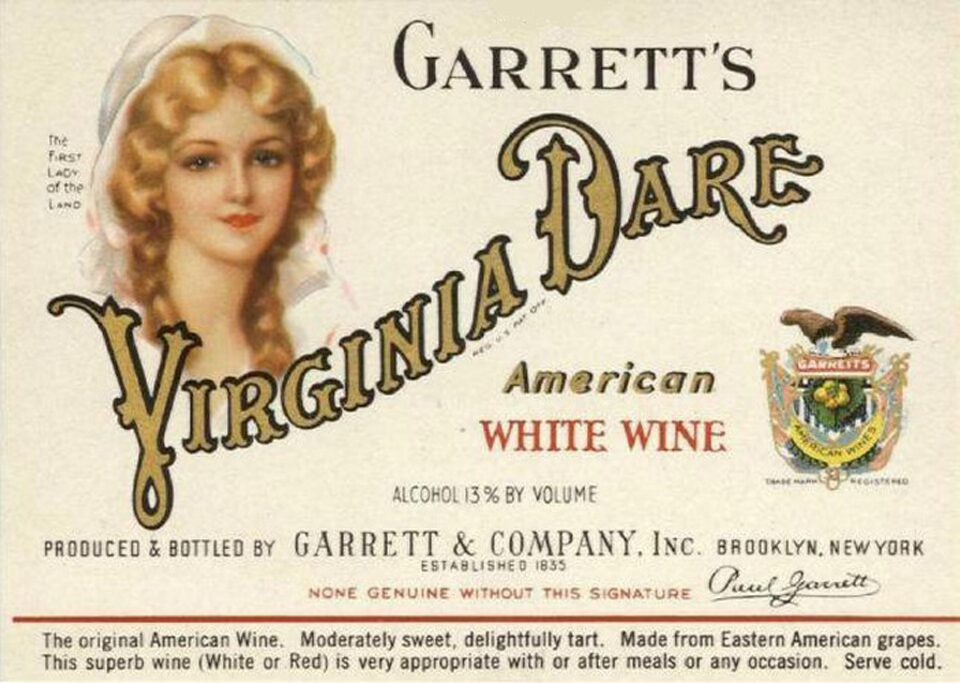

Before prohibition, North Carolina was one of the leading wine manufacturing states in the country, an industry that is now only slowly creeping back to being an important one for the state. The leading light in this industry wad Garrett & Company, whose line of scuppernong wines were among the most popular blends of wine in America. That line was called Virginia Dare wines.

Distributing Cotten’s book was part of an innovative and aggressive marketing campaign by Garret & Company to promote those scuppernong blends named for the lost colonist. Garret & Co. wanted to build the brand recognition for their sweet wines, as well as expand the appeal of their wines to women. They thought that a romantic, patriotic story was just the thing to encourage women to drink more cheap wine, and so they commissioned the poem from Ms. Cotten and gave the book away with bottles of their wine. Tying the legend of Virginia Dare in with a romantic origin myth for the scuppernong grape was entirely Sallie Southall Cotten’s invention. As for the poem itself, while Cotten’s style might been seen as stilted to modern eyes, the poem could probably easily hold its own against any other book-length poems advertising wine.

Ms. Cotten’s legend has outlasted the memory of its origins as an advertising campaign, and even outlasted the wine itself. Although Virginia Dare wines were the first wines advertised on radio, and the tagline in their advertisements, “Say it again — Virginia Dare,” was heard often enough during the 1920s to become one of the first famous radio catchphrases, prohibition was a blow form which Garet & Company never recovered.

When the ban on alcohol sales was lifted in 1929, Virginia Dare wines were the first American-made wines that were once again commercially available. But the company never regained its former glory. Garret & Company folded in the 1950s. But some of the last bottles of Virginia Dare wine made in the late 1940s have a possible connection to another, very different, American legend. These bottles are a much sought-after item by collectors, due to unverified rumors that the model posing for the portrait of Virginia Dare on the label was a young Marilyn Monroe.